In the northern Benin communities of Wèrèkè, Pouraparé, and Sonoumon, many people rely on agriculture for food and income. As the climate changes, natural ecosystems are pressured, and biodiversity is lost; crops suffer; and people’s food security and livelihoods diminish. With our partner Alafia and members of these three communities, we surveyed the biodiversity in preparation for establishing agroforestry plots that restore local ecosystems, sustain native biodiversity, and increase climate resilience and agricultural yield.

This activity, called a BioBlitz, is a citizen science approach to biodiversity data collection. By participating in this research, community members reconnect to the benefits provided by their local ecosystems. The data they collect, combined with literature on the nearby Ouémé Supérieur forest and their own experience with the natural world, will help them design agroforestry systems.

To gather data, we partnered with members of mothers’ associations (AMEs), a model developed by World Education and expanded in Benin over the last 15 years. AMEs allow women to participate in community decision-making, build economic resilience, invest in education, and contribute to environmental conservation. Through the Women-led, School-based Agroforestry Initiative, we are supporting AMEs to generate income through agroforestry.

Agroforestry is a land-sharing method in which intercropping plant species creates a forest ecosystem that attracts and sustains native biodiversity. This practice improves the sustainability and resilience of land use, while meeting the needs of humans.

The BioBlitz process started with community discussions on biodiversity, agriculture, and people’s perceptions of the natural world. They discussed the need for forest and agricultural land upkeep; the benefits of certain fauna species, soil richness, and temperature regulation found in the forest; and the climate events and pests threatening crops.

The communities then reflected on ecosystem services and how they benefit agriculture. They concluded that it would be valuable to replicate the ecosystem services provided by native forest in their agriculture systems.

The communities selected four sites for surveying, each with different compositions of crops and native flora:

- Monoculture: One crop species, in this case soybean.

- Polyculture: Diversity of perennial crop species and native trees and shrubs.

- Native forest: Abundance of wild tree and shrub species; no crop species.

- Fallow: Former crop land used for grazing cattle and sheep, herbaceous plants with no crops, and minimal trees.

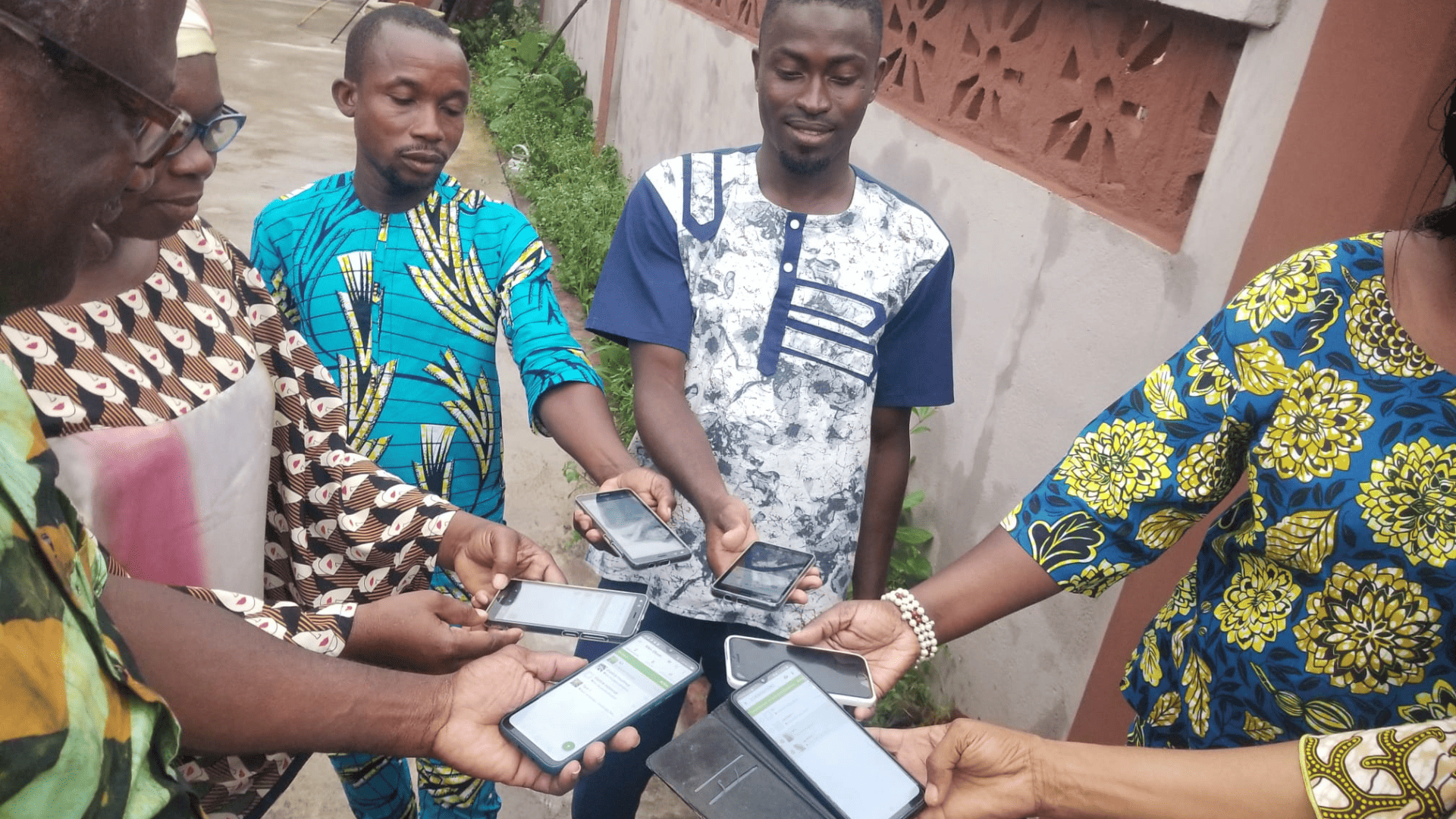

BioBlitz volunteers divided into four teams with designated roles. As the community members surveyed the sites, they documented observations through photos, sound bytes, and other methods in the iNaturalist app.

After gathering data, the communities convened to discuss anecdotal observations and perspectives of each site. They identified a number of trends:

- The polyculture site contained the most insects; the native forest the fewest.

- Nobody recalled seeing pests in the forest, but did observe numerous butterflies and birds, both deemed beneficial.

- Most of the insects present in the monoculture site were pests.

- On the fallow land site, many observed a correlation between the presence of trees at the edges of the pastures and a decrease in the number of grasshoppers.

- Potential correlation between the increased presence of birds and a decrease in the presence of grasshoppers.

The key takeaway for each community was that the presence of a diversity of species meant that pests were more controlled.

The agroforestry project team corroborated the anecdotal observations with scientific data collected in the BioBlitz, conducting a number of analyses on the abundance and richness of species groups, and presented the data back to the communities.

The data enabled communities to further reflect on their observations, and set the stage for them to design their agroforestry systems to include native tree species and those traditionally used for medicine. One day, the agroforestry systems may replicate the ecosystem services and socio-cultural benefits provided by native forests and that the communities observed and surveyed during the BioBlitz.